Introduction

Any dive into the inner workings of Node.js cannot be complete without discussing event loops. The first sentence of About Node.js highlights this without the reader realizing it.

As an asynchronous event-driven JavaScript runtime, Node.js is designed to build scalable network applications. [1]

The idea of an asynchronous, event-driven runtime is the bedrock of Node.js, and one of the many reasons why it has become so popular today. [2] One of the core pieces of the runtime, and likely most discussed piece, is the event loop. [3] It is the heart of Node.js and will be the centerpiece of this article. The event loop is composed of many pieces, but at its core is a library called libuv. [4] As with any library, the content in this article may drift towards incorrect over time. When I initially produced this content in late 2019, it required several changes to update it for 2025. This article has been drafted with a lens for libuv v1.x, specifically around the time of v1.51.0. This will provide an incomplete picture, and if the reader finds themselves wanting for more details, I strongly encourage also reading the documentation the library provides.

What is libuv?

Libuv arose as an abstraction over libev [5], which itself was modeled after libevent. [6] All of which are themselves abstractions over system calls like select, poll, or event notification interfaces like epoll and kqueue. In the library’s own words, libuv can be referred to as a…

multi-platform support library with a focus on asynchronous I/O [4]

To the keen reader, this will sound very much like our asynchronous, event-driven runtime, we’ve just replaced event-driven with I/O. Which is to say the concepts that drive libuv and Node.js are one and the same. Before we discuss those concepts, I want to take the time to highly the large number of features within the library:

- Full-featured event loop backed by epoll, kqueue, IOCP, event ports.

- Asynchronous TCP and UDP sockets

- Asynchronous DNS resolution

- Asynchronous file and file system operations

- File system events

- ANSI escape code controlled TTY

- IPC with socket sharing, using Unix domain sockets or named pipes (Windows)

- Child processes

- Thread pool

- Signal handling

- High-resolution clock

- Threading and synchronization primitives

The majority of which I will not be tackling in this article. I would like to draw attention to what I believe is the main feature of Node.js:

Full-featured event loop backed by epoll, kqueue, IOCP, event ports.

There will be discussion of other features in order to fully encapsulate what it means to run an event loop, but my primary focus will be to help the reader gain a deeper understanding of the event loop provided by libuv.

The Event Loop

An event loop is a design pattern that focuses on the control flow of events. The loop will perform requests from events by invoking handlers associated with those events. This type of design pattern often arises in single-threaded environments, but is not limited to it. Node.js is often incorrectly described a single-threaded system and this misnomer arises from the use of the event loop pattern. libuv describes their event loop in the following way:

The event loop is the central part of libuv’s functionality. It takes care of polling for I/O and scheduling callbacks to be run based on different sources of events

There are many styles for event loops, libuv’s particular application is based on the Reactor Pattern. [7] And libuv is not the only application of this pattern, systems like nginx, Netty, Spring, Tokio and Twisted all arose as applications of it. It has proven to be a strong design pattern for I/O handling in particular. Libuv puts its own special twist on the idea by breaking the event loop into phases, those being:

- Timer

- Pending

- Idle

- Prepare

- I/O

- Check

- Close

These phases are represented both in the internal data structures, as well as the looping code itself. As a note, I find one of the best ways to deeply understand ideas to be looking at code. There’s a great deal happening in the libuv codebase, so I will endeavor to summarize as best I can. The majority of the code we will be looking at is written in C. I find it’s written well enough that most with a programming background should be able to understand it at a glance. So, let’s start by looking at a representation of the event loop in libuv. This is one of the primary data structures in the library and is used to create the loop referenced throughout the code.

typedef struct uv__loop_s uv__loop_t;

struct uv_loop_s {

void* data;

unsigned int active_handles;

struct uv__queue handle_queue;

union {

void* unused;

unsigned int count;

} active_reqs;

void* internal_fields;

unsigned int stop_flag;

UV_LOOP_PRIVATE_FIELDS

};As an author’s note, you may see the pattern on <name>_s and <name>_t used interchangeably. If you ever see the former when you expected the latter, or vice versa, know that they represent the same thing. While this struct definition gives us some insight, it’s not as useful without breaking down the tail end of the struct definition, given by UV_LOOP_PRIVATE_FIELDS. This is where the interesting pieces of the struct start to come into view. As an additional note, libuv is multi-platform and has both Unix and Windows support. I have a strong proclivity for Unix systems, so when we are presented with multiple options for a snippet of code, I have chosen to look at the Unix variant. This Unix variant for UV_LOOP_PRIVATE_FIELDS can be summarized like so:

#define UV_LOOP_PRIVATE_FIELDS

/*...skipped fields */

struct uv__queue pending_queue;

struct uv__queue watcher_queue;

uv__io_t** watchers;

/*...skipped fields */

uv_mutex_t wq_mutex;

uv_async_t wq_async;

uv_rwlock_t cloexec_lock;

uv_handle_t* closing_handles;

struct uv__queue process_handles;

struct uv__queue prepare_handles;

struct uv__queue check_handles;

struct uv__queue idle_handles;

struct uv__queue async_handles;

/*...skipped fields */

struct {

void* min;

unsigned int nelts;

} timer_heap;

/*...skipped fields */As you can see, there are a number of fields not represented here, because even with the qualifier of Unix-focused code there is significant variety in the compilation targets. What I do want to call out is the handles, which are prefixed with the phase names they correspond to. There is one outstanding question here though, where is the I/O management? Libuv is, after all, fundamentally an I/O management library. The vast majority of the I/O-related data structures can be found in uv__io_t.

typedef struct uv__io_s uv__io_t;

struct uv__io_s {

uintptr_t bits;

struct uv__queue pending_queue;

struct uv__queue watcher_queue;

unsigned int pevents; /* Pending event mask i.e. mask at next tick. */

unsigned int events; /* Current event mask. */

int fd;

UV_IO_PRIVATE_PLATFORM_FIELDS

};A large part of the management of I/O will be in a kernel system, and as such, we will take this simplified view for now as we progress. We will explore the use of these data structures as we iterate through the various phases of the event loop. However, we will stop short of system call handling. With that boundary in place, we have a view of the data, but data alone does not make a program, we need control as well. So what does the execution of the event loop look like?

int uv_run(uv_loop_t* loop, uv_run_mode mode) {

/*...skipped logic */

if (!r)

uv__update_time(loop);

/*...skipped logic */

while (r != 0 && loop->stop_flag == 0) {

/*...skipped logic */

uv__run_pending(loop);

uv__run_idle(loop);

uv__run_prepare(loop);

/*...skipped logic */

uv__io_poll(loop, timeout);

/*...skipped logic */

uv__run_check(loop);

uv__run_closing_handles(loop);

uv__update_time(loop);

uv__run_timers(loop);

/*...skipped logic */

}

/*...skipped logic */

return r;

}As you can see, there is again a suffix indicating the phase that the function corresponds to. I want to call special attention to a particular aspect of the event loop, which is uv__update_time. One of the foundational components of the event loop is time. While a large part of the uv_loop_t data structure is dedicated to queues for handles, there is a core component called the timer_heap. The timer_heap is a min-heap data structure. [8] And a key part of the reliable running of timers is the concept of “now”, which is controlled, in part through uv__update_time. The event loop tries to maintain millisecond level tick precision in order to reliably execute timers. Let’s see now how we utilize this precision, and the phases more generally by exploring each phase in detail.

Phases of the Event Loop

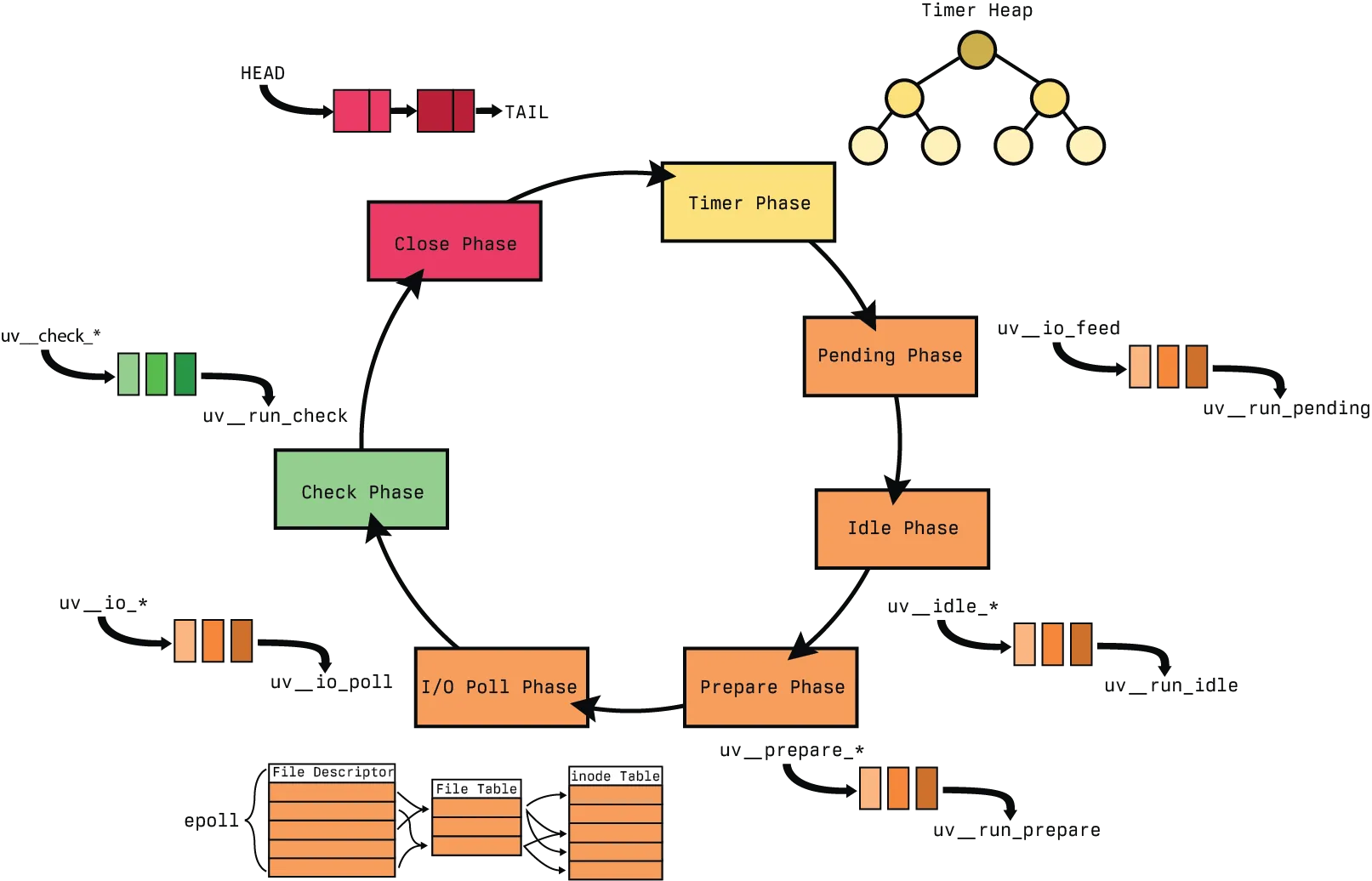

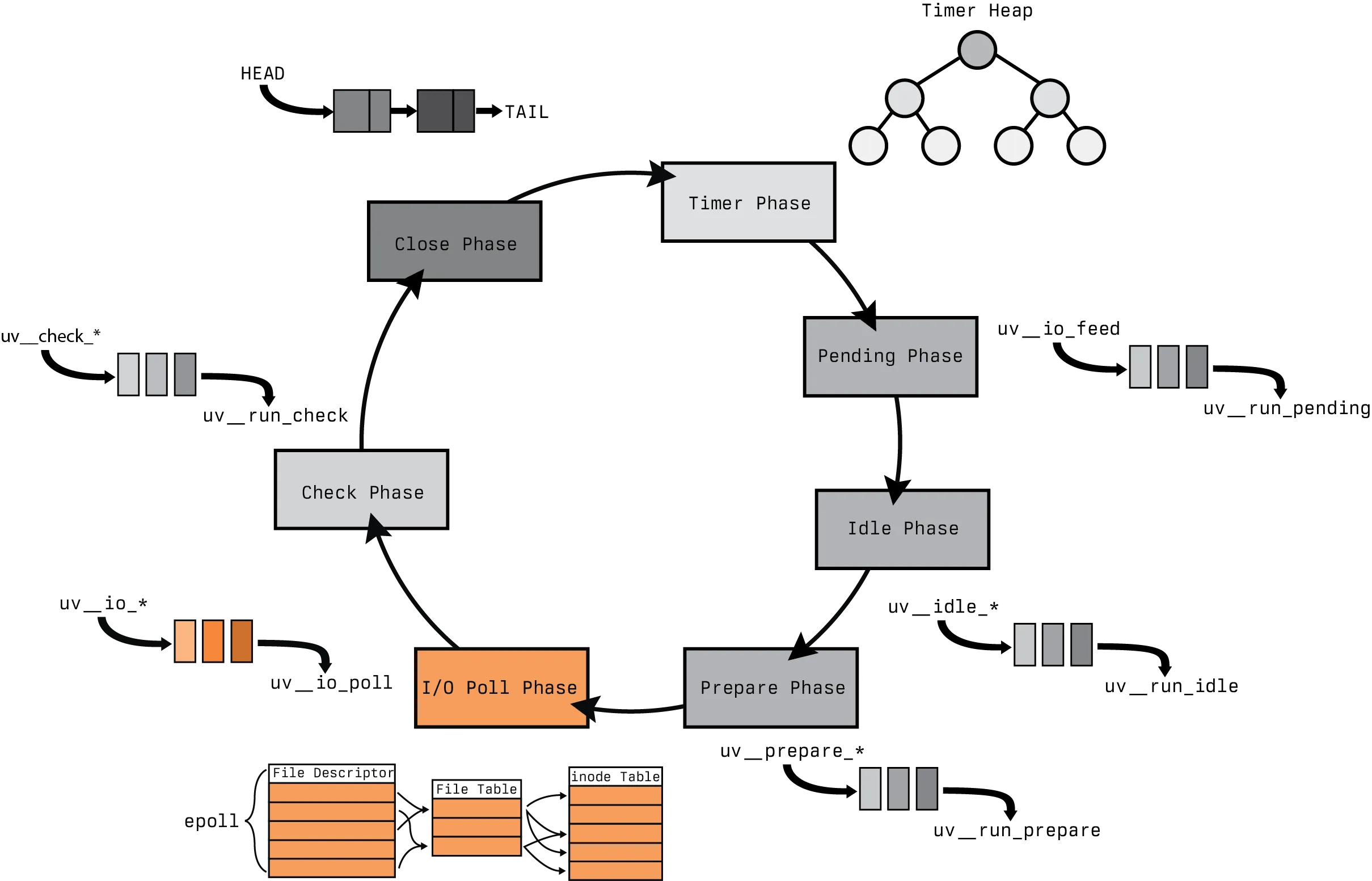

Node.js only has commonly been referred to as having only four phases, those being the phases associated setImmediate(), setTimeout(), I/O polling and closing. This isn’t completely correct, but we will be using this approximation as a visual tool for our subsequent diagrams. I find that illustrations tend to help guide the conversation in a structured manner. So as we discuss each phase, I would like to provide two images to guide an understanding. The first is a representation of the event loop itself, this is the graphical equivalent of uv_loop_t for Node.js. This highlights the core data structures in place, and collapse some of the phases to this approximate four phase set.

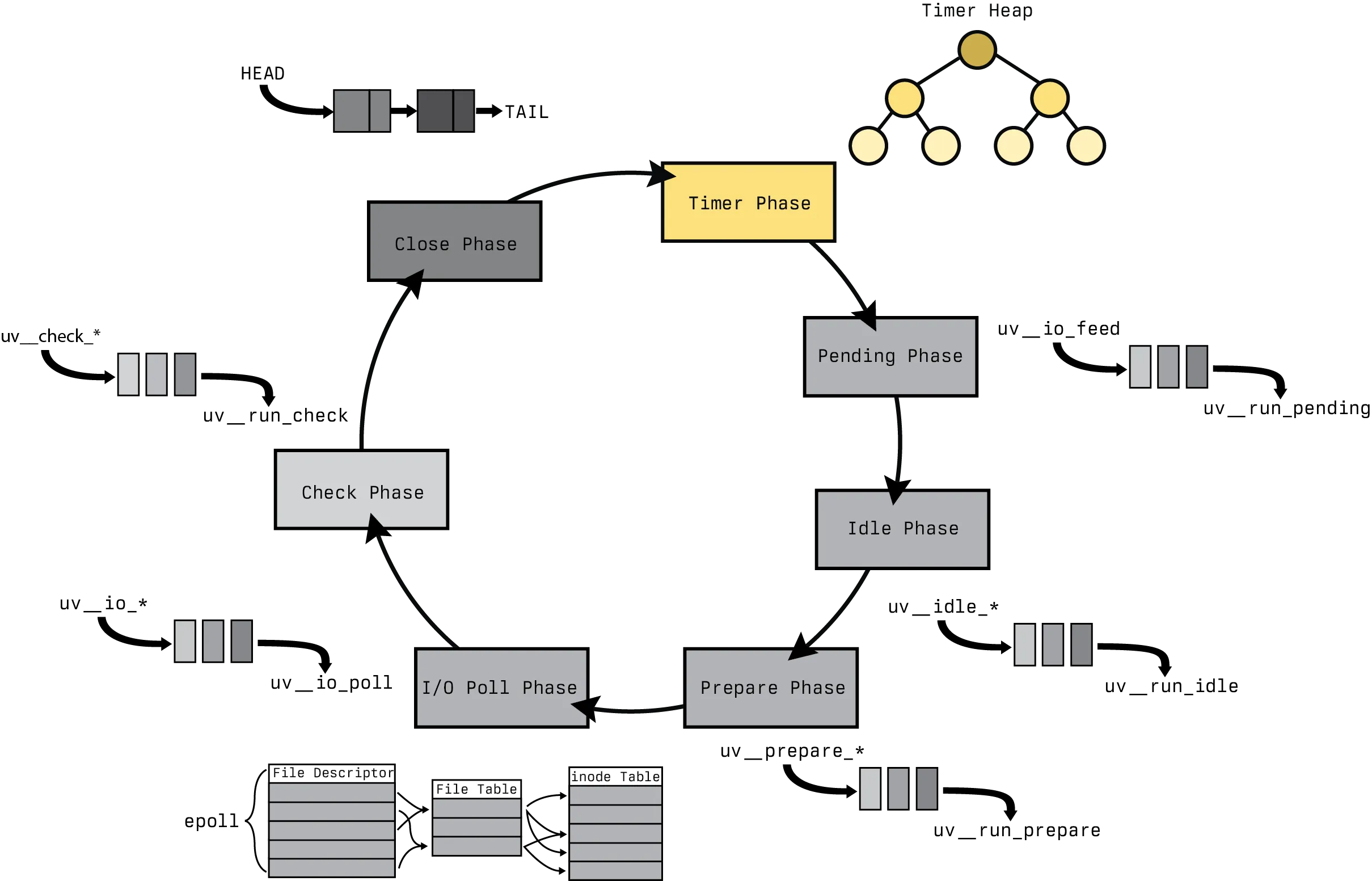

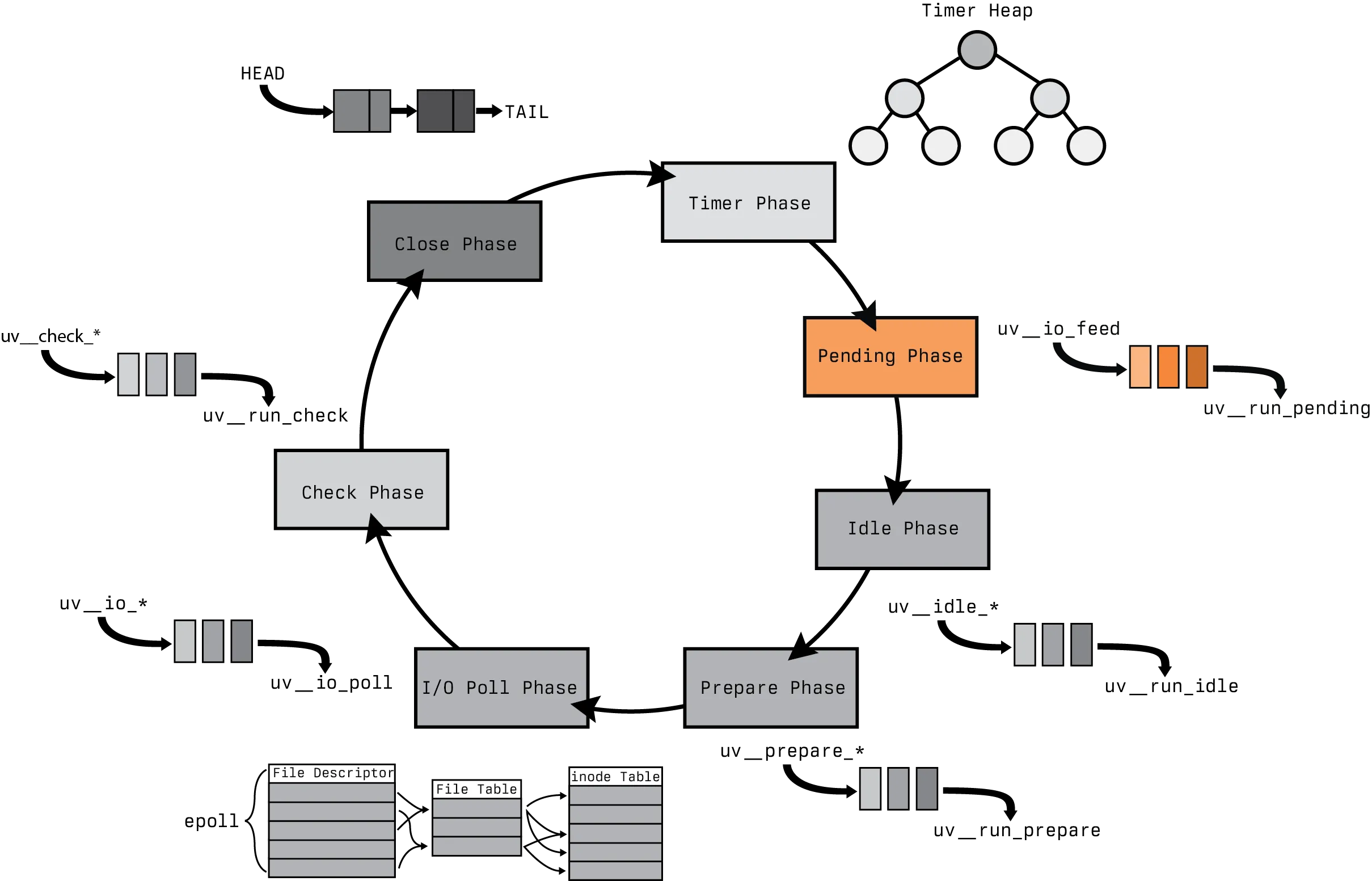

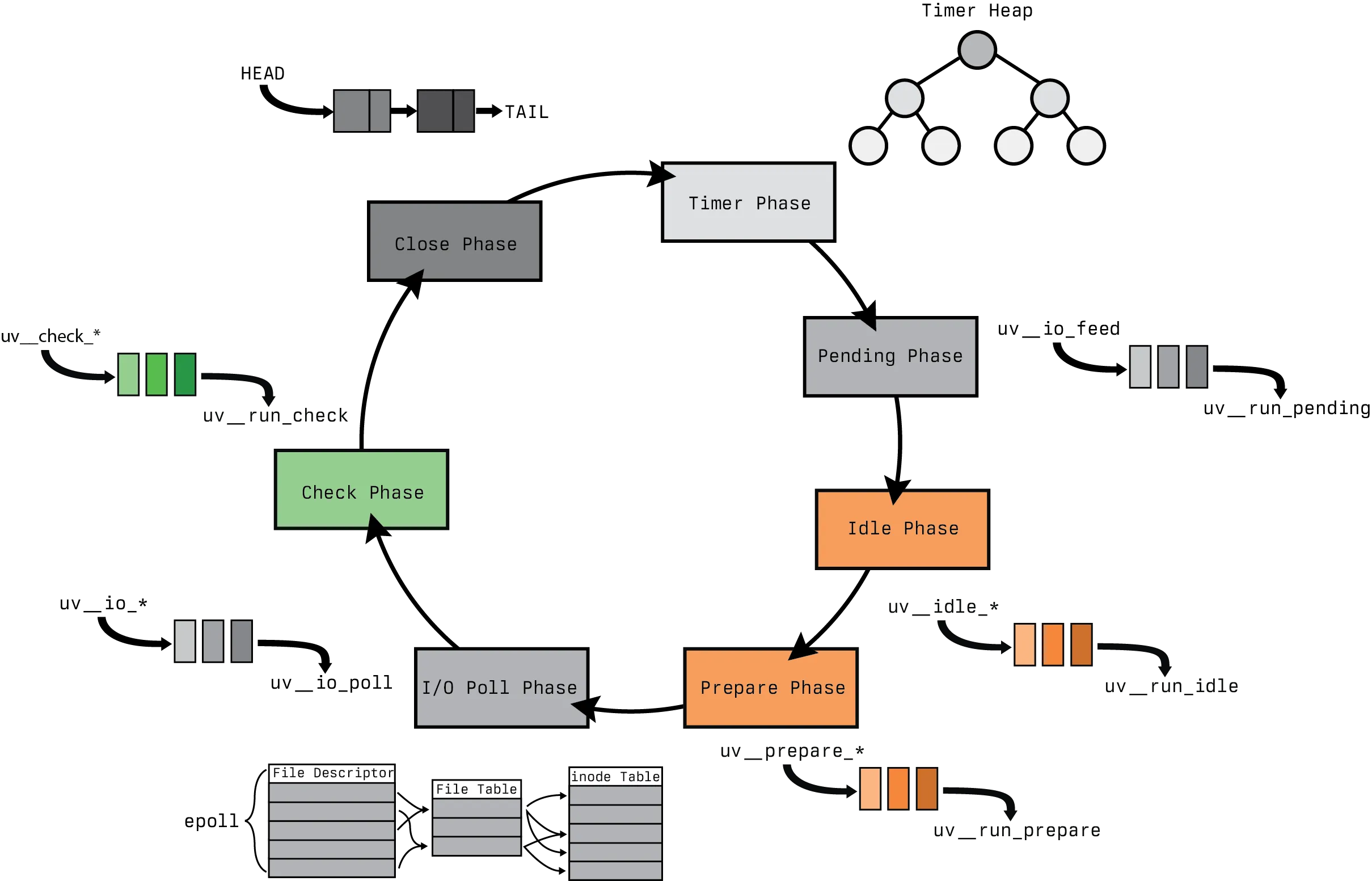

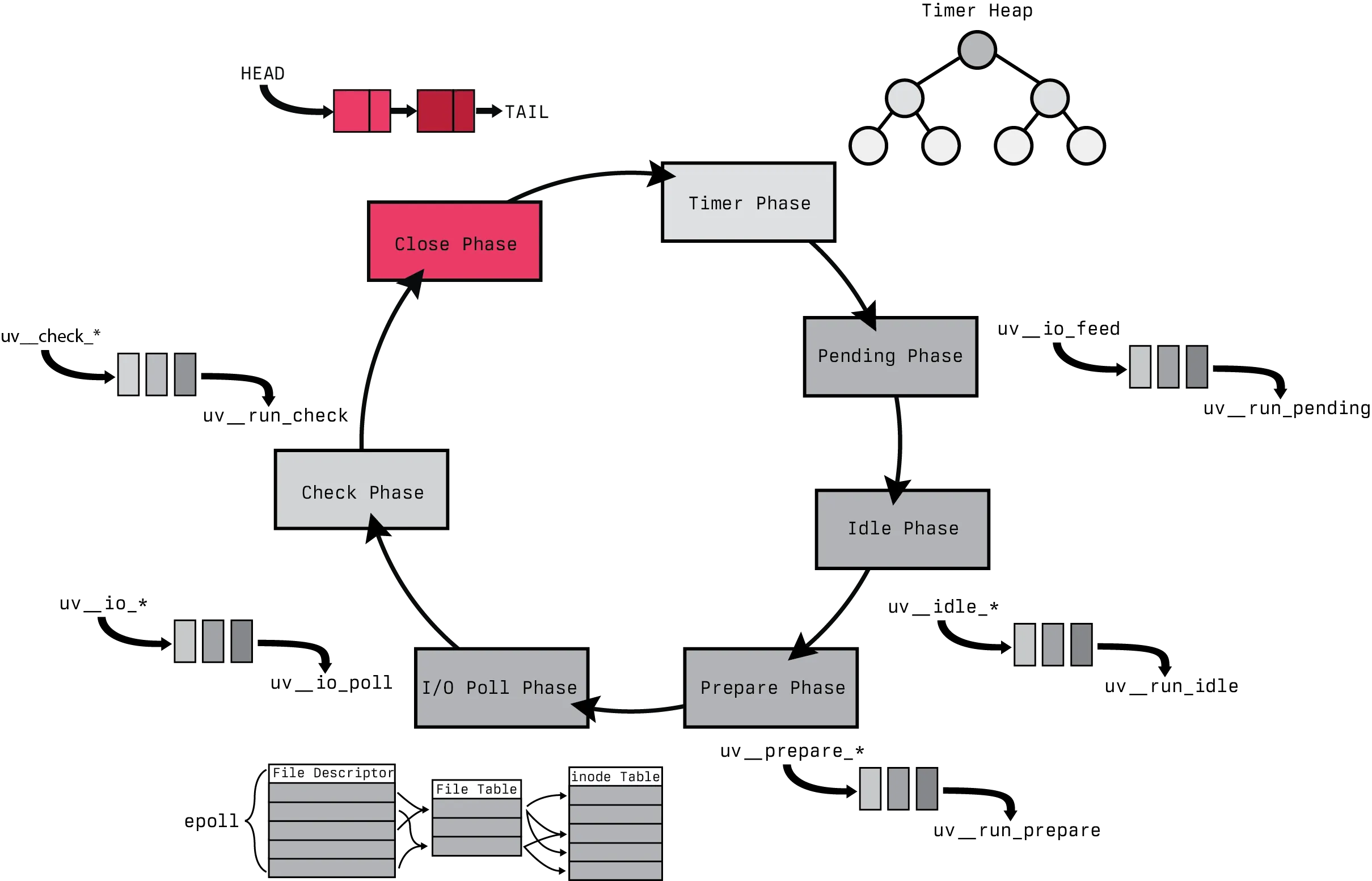

This diagram has several core data structures in play. There are queues, min-heaps, linked lists and tables. We will be discussing each of these in detail except for the tables and the center queue. For more information on that, you should read the epoll and promises post. This diagram is my own personal representation of the Node.js event loop. It applies beyond just the context of libuv and incorporates several other concepts that are vital to Node.js as well. However, since this is focused on libuv, so let’s isolate that diagram to just what we will be discussing through this post.

We have removed the data structure in the center have been removed and we have expanded some of the colored sections to incorporate all the individual phases that comprise it. We will be using this as our guide throughout the remainder of the post, but as you explore more node.js topics on the blog, keep the overall event diagram loop in mind.

Timer

The first phase we are going to look at is the timer phase. The timer phase effectively amounts to the execution of timer objects that have a handle time greater than the current loop time. The vast majority of the logic for this idea is contained within the data structure. Let’s recap what a min-heap is.

Heaps where the parent key is greater than or equal to (≥) the child keys are called max-heaps; those where it is less than or equal to (≤) are called min-heaps. Efficient (logarithmic time) algorithms are known for the two operations needed to implement a priority queue on a binary heap:

- inserting an element

- removing the smallest or largest element from a min-heap or max-heap

Binary heaps are also commonly employed in the heapsort sorting algorithm, which is an in-place algorithm because binary heaps can be implemented as an implicit data structure, storing keys in an array and using their relative positions within that array to represent child-parent relationships. [9]

The execution of the timers, for all intents and purposes, occurs at the beginning of the loop. The timer function definition can be seen below with the major stages being:

- Determine the timers ready to execute by checking the handle time against the loop time

- When a timer is ready to fire, the handle is removed from the heap

- Then it is passed to a queue for execution

void uv__run_timers(uv_loop_t* loop) {

struct heap_node* heap_node;

uv_timer_t* handle;

struct uv__queue* queue_node;

struct uv__queue ready_queue;

uv__queue_init(&ready_queue);

for (;;) {

heap_node = heap_min(timer_heap(loop));

if (heap_node == NULL)

break;

handle = container_of(heap_node, uv_timer_t, node.heap);

if (handle->timeout > loop->time)

break;

uv_timer_stop(handle);

uv__queue_insert_tail(&ready_queue, &handle->node.queue);

}

while (!uv__queue_empty(&ready_queue)) {

queue_node = uv__queue_head(&ready_queue);

uv__queue_remove(queue_node);

uv__queue_init(queue_node);

handle = container_of(queue_node, uv_timer_t, node.queue);

uv_timer_again(handle);

handle->timer_cb(handle);

}

}We close out the code with that ability to repeat timers, as seen in setInterval(func, delay). This simply adds the handle back to the heap if the repeat functionality is enabled.

Pending

The pending phase is the first of our queue structured phases. For the context of Node.js, it serves a specific purpose which we didn’t highlight in our original four phases.

This phase executes callbacks for some system operations such as types of TCP errors. For example if a TCP socket receives ECONNREFUSED when attempting to connect, some *nix systems want to wait to report the error. This will be queued to execute in the pending callbacks phase. [10]

Which, for most readers, this phase is not going to be the highlight of your exploration of the event loop. It’s purpose is focused and limited. The primary goal from a libuv standpoint is the execution of deferred I/O callbacks that were retrieved in the I/O polling phase. As such, you can see how Node.js arrived at this use for the management of TCP errors.

Which makes the pending phase is unique compared to it’s other queue handling phases. For most queue phases, when a callback is scheduled, there is a permanent data structure in the uv_loop_t that tracks the handles, but this phase is unique in that it tracks handles within the uv__io_t data structure.

static void uv__run_pending(uv_loop_t* loop) {

struct uv__queue* q;

struct uv__queue pq;

uv__io_t* w;

uv__queue_move(&loop->pending_queue, &pq);

while (!uv__queue_empty(&pq)) {

q = uv__queue_head(&pq);

uv__queue_remove(q);

uv__queue_init(q);

w = uv__queue_data(q, uv__io_t, pending_queue);

uv__io_cb(loop, w, POLLOUT);

}

}The code is simplistic from a surface view. Fundamentally, we are retrieving the head of the queue, removing the value, adding data to the uv_io_t data structure, then executing the callback. The uv__io_cb() function is where a great deal of the complexity lies. We will discuss the management of I/O in greater detail in the I/O Phase section.

Idle, Prepare and Check

The idle, prepare and check function the same, and very similarly to the pending phase. They rely on the on a queue data structure for processing events. As a result of the similar nature, we will be discussing them together. Each of the phases represents a different idea however. From the standpoint of Node.js, the check phase is associated with the setImmediate() callback, and the idle and prepare phase are both unused.

The code for these phases are defined in the same macro, the UV_LOOP_WATCHER_DEFINE macro. The majority of it has been truncated to just the uv_run related functionality.

#define UV_LOOP_WATCHER_DEFINE(name, type)

/*... skipped functions */

void uv__run_##name(uv_loop_t* loop) {

uv_##name##_t* h;

struct uv__queue queue;

struct uv__queue* q;

uv__queue_move(&loop->name##_handles, &queue);

while (!uv__queue_empty(&queue)) {

q = uv__queue_head(&queue);

h = uv__queue_data(q, uv_##name##_t, queue);

uv__queue_remove(q);

uv__queue_insert_tail(&loop->name##_handles, q);

h->name##_cb(h);

}

}This code needs very little exploration with it, as it pulls from the head of the queue, retrieves the requisite element data, removes the element from the queue, then processes the callback associated. There is one deviation from the Pending phase for the insertion of the tail into the handles queue for the associated h->name. This is the mechanism that the event loop uses for determining if active handles are present for the Idle phase, in order to determine if the event loop can sleep or not. The Idle phase is a bit special in this sense. It might actually be more accurate to refer to it as the Spin phase. As it’s primary responsibility is to keep the event loop spinning.

I/O Poll

The I/O Poll, or commonly just poll, phase is the most complex of all the phases, the run function alone is over 200 lines. As with the other variants, there are a number of possibilities to look at, we will be focusing on the Linux version which utilizes epoll. However, we will not be looking at the data structures associated or system calls with this phase. The data structures are predominantly inherit to the system calls related to epoll.

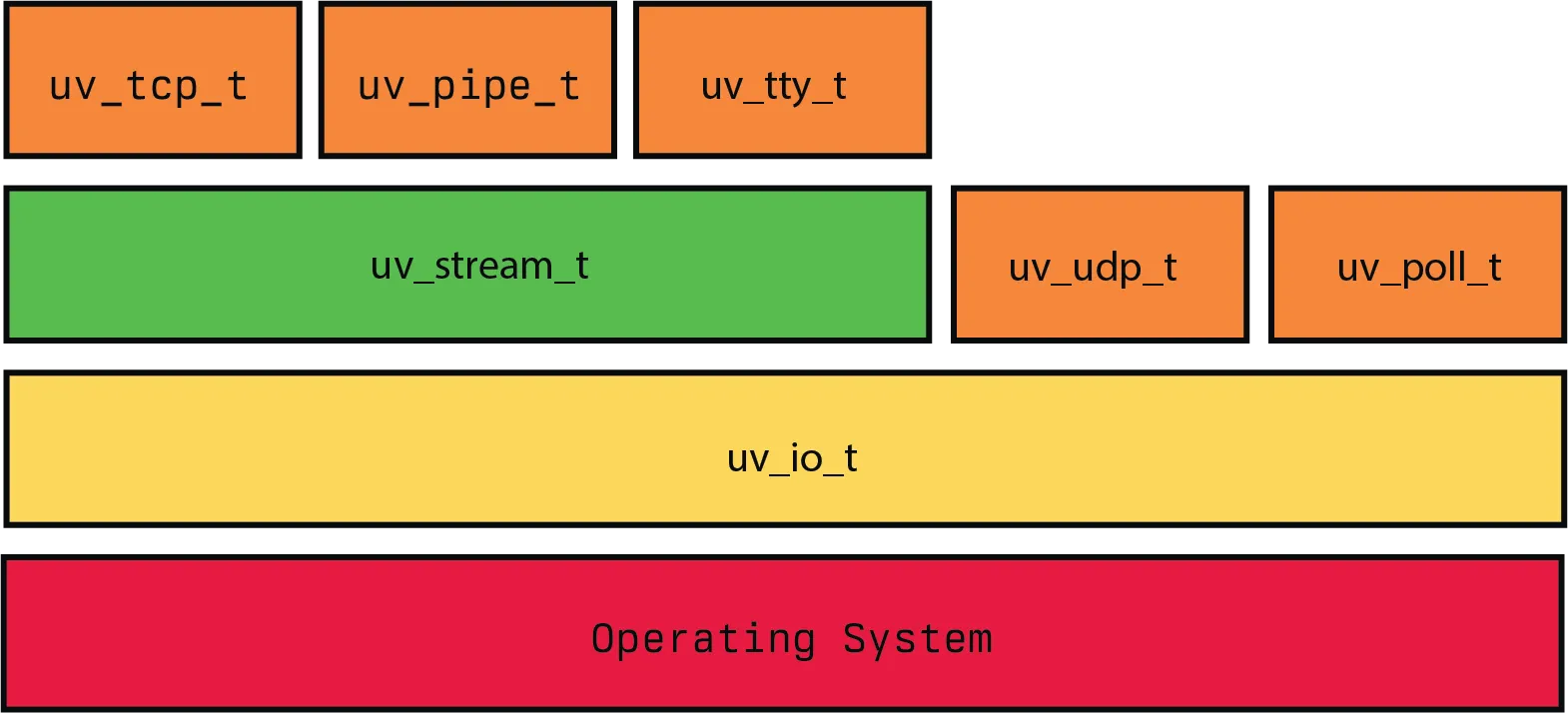

This is represented in part in the diagram as the only phase with technically four data structures associated with it. Three of which are deeply related. The semantics of epoll and how it processes information related to data is a topic for a different post. We will focused on the abstractions that libuv processed over this concept, specifically related to the networking stack. You can see libuv’s networking stack in the image below.

That is to say we have three layers of abstraction. uv_stream_t encompasses the concepts of TCP, TTY and Pipes, represented by uv_tcp_t, uv_tty_t and uv_pipe_t respectively. This is joined by two additional non-stream concepts, uv_udp_t and uv_ping_t to form all the components of uv_io_t. This is the same data structure we started the post with. This is all built on a foundation of the various operating system components, which in the case of Linux is in part managed by epoll.

void uv__io_poll(uv_loop_t* loop, int timeout) {

/* ... data structure definitions */

epollfd = loop->backend_fd;

/* ... skipped code */

while (!uv__queue_empty(&loop->watcher_queue)) {

q = uv__queue_head(&loop->watcher_queue);

w = uv__queue_data(q, uv__io_t, watcher_queue);

uv__queue_remove(q);

uv__queue_init(q);

op = EPOLL_CTL_MOD;

if (w->events == 0)

op = EPOLL_CTL_ADD;

w->events = w->pevents;

e.events = w->pevents;

e.data.fd = w->fd;

fd = w->fd;

if (ctl->ringfd != -1) {

uv__epoll_ctl_prep(epollfd, ctl, &prep, op, fd, &e);

continue;

}

if (!epoll_ctl(epollfd, op, fd, &e))

continue;

/* ... edge cases skipped */

}

inv.events = events;

inv.prep = &prep;

inv.nfds = -1;

for (;;) {

if (loop->nfds == 0)

if (iou->in_flight == 0)

break;

/* All event mask mutations should be visible to the kernel before

* we enter epoll_pwait().

*/

if (ctl->ringfd != -1)

while (*ctl->sqhead != *ctl->sqtail)

uv__epoll_ctl_flush(epollfd, ctl, &prep);

uv__io_poll_prepare(loop, NULL, timeout);

nfds = epoll_pwait(epollfd, events, ARRAY_SIZE(events), timeout, sigmask);

uv__io_poll_check(loop, NULL);

/* ... timeout management and error handling */

have_iou_events = 0;

have_signals = 0;

nevents = 0;

inv.nfds = nfds;

lfields->inv = &inv;

for (i = 0; i < nfds; i++) {

pe = events + i;

fd = pe->data.fd;

/* Skip invalidated events, see uv__platform_invalidate_fd */

if (fd == -1)

continue;

if (fd == iou->ringfd) {

uv__poll_io_uring(loop, iou);

have_iou_events = 1;

continue;

}

assert(fd >= 0);

assert((unsigned) fd < loop->nwatchers);

w = loop->watchers[fd];

if (w == NULL) {

/* File descriptor that we've stopped watching, disarm it.

*

* Ignore all errors because we may be racing with another thread

* when the file descriptor is closed.

*

* Perform EPOLL_CTL_DEL immediately instead of going through

* io_uring's submit queue, otherwise the file descriptor may

* be closed by the time the kernel starts the operation.

*/

epoll_ctl(epollfd, EPOLL_CTL_DEL, fd, pe);

continue;

}

/* Give users only events they're interested in. Prevents spurious

* callbacks when previous callback invocation in this loop has stopped

* the current watcher. Also, filters out events that users has not

* requested us to watch.

*/

pe->events &= w->pevents | POLLERR | POLLHUP;

/* Work around an epoll quirk where it sometimes reports just the

* EPOLLERR or EPOLLHUP event. In order to force the event loop to

* move forward, we merge in the read/write events that the watcher

* is interested in; uv__read() and uv__write() will then deal with

* the error or hangup in the usual fashion.

*

* Note to self: happens when epoll reports EPOLLIN|EPOLLHUP, the user

* reads the available data, calls uv_read_stop(), then sometime later

* calls uv_read_start() again. By then, libuv has forgotten about the

* hangup and the kernel won't report EPOLLIN again because there's

* nothing left to read. If anything, libuv is to blame here. The

* current hack is just a quick bandaid; to properly fix it, libuv

* needs to remember the error/hangup event. We should get that for

* free when we switch over to edge-triggered I/O.

*/

if (pe->events == POLLERR || pe->events == POLLHUP)

pe->events |=

w->pevents & (POLLIN | POLLOUT | UV__POLLRDHUP | UV__POLLPRI);

if (pe->events != 0) {

/* Run signal watchers last. This also affects child process watchers

* because those are implemented in terms of signal watchers.

*/

if (w == &loop->signal_io_watcher) {

have_signals = 1;

} else {

uv__metrics_update_idle_time(loop);

uv__io_cb(loop, w, pe->events);

}

nevents++;

}

}

/* ... signaling and timeout */

}

if (ctl->ringfd != -1)

while (*ctl->sqhead != *ctl->sqtail)

uv__epoll_ctl_flush(epollfd, ctl, &prep);

}The code to manage all of this, including epoll is reasonably long, but not very complex. We start with our normal queue management for any watched events. From there, we perform some case management around previously watched file description and we ensure that anything in our watched queue is also watched by epoll through either add or modify flags. After we have handled all the incoming watch queue items, we start in an infinite loop. The loop does the following…

- Find all file descriptors with changes

- Process the events with the I/O callback handler

- Continue until there are no more file descriptors to process

That simplifies the loop quite a bit as there is a fair bit of epoll management, but for all intents and purposes that’s enough for understanding the libuv portion. The main difference between this phase and other phases is that each phase is explicitly told what to do before it even starts, this is the only phase that needs to ask an external source about what it needs to perform. As a note, the File I/O functions slightly different than this, as the blocking File I/O operations rely on a threadpool. [11]

Close

The final is the closing handles. From the context of Node.js, this is responsible for closing of resources.

If a socket or handle is closed abruptly (e.g. socket.destroy()), the ‘close’ event will be emitted in this phase. Otherwise it will be emitted via process.nextTick(). [3]

For libuv, this amounts to processing a linked list of events. These individual handles are operating system specific, but the data structure associated can be seen below.

#define UV_HANDLE_FIELDS

/* public */

void* data;

/* read-only */

uv_loop_t* loop;

uv_handle_type type;

/* private */

uv_close_cb close_cb;

struct uv__queue handle_queue;

union {

int fd;

void* reserved[[4]];

} u;

UV_HANDLE_PRIVATE_FIELDS

/* The abstract base class of all handles. */

struct uv_handle_s {

UV_HANDLE_FIELDS

};In the general sense, they are file descriptors that need to be closed. These could be network connections, open files, or any number of relevant I/O systems that the operating system is capable of handling. The processing of these events is simple on the surface.

static void uv__run_closing_handles(uv_loop_t* loop) {

uv_handle_t* p;

uv_handle_t* q;

p = loop->closing_handles;

loop->closing_handles = NULL;

while (p) {

q = p->next_closing;

uv__finish_close(p);

p = q;

}

}That is to say, we get all the closing handles on a loop, and loop through them performing the uv__finish_close() function on each. The uv__finish_close() function and only has a few key pieces to handle. These break down into:

- If events are trapped for a handle, process them in the pending phase

- If we are closing a stream, run the

uv__stream_destroy() - If we are closing a UDP connection, run the

uv__udp_finish_close - Remove the event from the handle queue

This is given in the following code snippet.

static void uv__finish_close(uv_handle_t* handle) {

uv_signal_t* sh;

/* Note: while the handle is in the UV_HANDLE_CLOSING state now, it's still

* possible for it to be active in the sense that uv__is_active() returns

* true.

*

* A good example is when the user calls uv_shutdown(), immediately followed

* by uv_close(). The handle is considered active at this point because the

* completion of the shutdown req is still pending.

*/

assert(handle->flags & UV_HANDLE_CLOSING);

assert(!(handle->flags & UV_HANDLE_CLOSED));

handle->flags |= UV_HANDLE_CLOSED;

switch (handle->type) {

case UV_PREPARE:

case UV_CHECK:

case UV_IDLE:

case UV_ASYNC:

case UV_TIMER:

case UV_PROCESS:

case UV_FS_EVENT:

case UV_FS_POLL:

case UV_POLL:

break;

case UV_SIGNAL:

/* If there are any caught signals "trapped" in the signal pipe,

* we can't call the close callback yet. Reinserting the handle

* into the closing queue makes the event loop spin but that's

* okay because we only need to deliver the pending events.

*/

sh = (uv_signal_t*) handle;

if (sh->caught_signals > sh->dispatched_signals) {

handle->flags ^= UV_HANDLE_CLOSED;

uv__make_close_pending(handle); /* Back into the queue. */

return;

}

break;

case UV_NAMED_PIPE:

case UV_TCP:

case UV_TTY:

uv__stream_destroy((uv_stream_t*)handle);

break;

case UV_UDP:

uv__udp_finish_close((uv_udp_t*)handle);

break;

default:

assert(0);

break;

}

uv__handle_unref(handle);

uv__queue_remove(&handle->handle_queue);

if (handle->close_cb) {

handle->close_cb(handle);

}

}You can see our prior references to pending for errors, as well as the relatively simple closing handles, queue management, callback mechanisms we have seen previously and case specific handling.

Summary

This article, and it’s related articles, started as a teach out session around early-2020 for developers interested in starting to develop in Node.js. The goal was to teach the intricacies of the platform in a way that broke down a complex asynchronous event system, into a digestable procedurable based approach. The libuv library has a great deal more than what was explored here. We only tackled a fraction of the functionality by glimpsing into the core of the code. This core is encompassed by 7 distinct phases of processing: timers, pending, idle, prepare, io, check and close. However, Node.js effectively only utilize four of these phases, with a fifth being used for a unique edge case. If you find yourself with an interested in exploring more deeply, the following is a list of valuable content that wasn’t directly referenced. This list, in addition to the reference content, helped solidify my understanding of the event loop.

- Event loop in JavaScript

- NodeConf EU | A deep dive into libuv

- rough notes on the linux side of the libuv event loop

- The Node.js Event Loop: Not So Single Threaded

- Morning Keynote - Everything You Need to Know About Node.js Event Loop

- All you need to know to really understand the Node.js Event Loop and its Metrics

- Node’s Event Loop From the Inside Out

- Nonblocking I/O

References

- https://nodejs.org/en/about/

- https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2025/technology#most-popular-technologies

- https://nodejs.org/en/docs/guides/event-loop-timers-and-nexttick

- https://github.com/libuv/libuv

- https://github.com/enki/libev

- https://github.com/libevent/libevent

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reactor_pattern

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Min-max_heap

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binary_heap

- https://nodejs.org/en/learn/asynchronous-work/event-loop-timers-and-nexttick#pending-callbacks

- https://blog.libtorrent.org/2012/10/asynchronous-disk-io/